The road through the little town of Pont l’Abbe d’Arnoult. That basket shop is no longer there, but I used to pop in regularly as it sold all sorts of odds and sods. Opposite was a small supermarket. The post office was at the other end of the place, boasting the most unfriendly and po-faced post mistress in the world! The arch and the church on just the other side date back to the 14th Centuries; the church has a very ornate portico which is unusual because most of the churches in the area were fortified against the English during the Hundred years’ War and look somewhat bulky and plain.

We moved the children to a little privately-run Roman Catholic school in the small market town of Pont l’Abbe, which was to be some 15-20 minutes’ drive from our new house. We had rapidly learnt that, although the village school we were leaving was undoubtledly quite excellent in its own way (despite only 2 hole-in-the-ground toilets for 105 children), it taught the children very little apart from how to speak bad (ie local) French and how to aspire to becoming a farm labourer. We decided therefore that the village school in our new village, Ste Justine, although it was probably all very sweet and delightfully dated, was not for our kids. I have to confess that we didn’t even look round it.

Driving the children to school in the winter was often so lovely, with a mist shrouding everything but the church spire. The name of the town has nothing to do with an abbey, as one might suppose, though there is an abbey in nearby Trizay, about 5 miles east. Apparently there used to be a bridge (pont) at a homestead either named Abe or the owner was named Abe, circa 1200 or so, before the town was built. That is how the name evolved, l’Arnoult being the name of the river.

The Pont l’Abbe d’Arnoult school was not a fee-paying school in the UK sense, where independent schools can be excruciatingly expensive. This was not the same thing at all – the fees were really nothing much, even for three children. It did, however, have a better standard and the children started to mix with “better” other children – note use of inverted commas. The fact that it was RC was by-the-by. There was a chapel, and a couple of nuns fluttering about occasionally, but it was otherwise an ordinary school. As is the way in most schools on the continent, there was no uniform, and it was particularly from the children’s clothes that one could tell we were in a completely different social bracket. Here the kids wore Rip Curl and similar makes, good quality shoes, and were always clean. At the school we had left the children were frequently grubby and their clothes even grubbier.

A bonus was that there were a few other foreign children already there – and English girl by the name of Charlotte, I recall, a couple of Australian girls and an American boy. This was a bonus not because we wanted the children to be able to speak in English but because, no longer being the only foreigners, they didn’t stick out like sore thumbs any more.

The last summer at Primrose. Me standing outside the kitchen/utility room door, with the 3 children and two friends. William always had zillions of friends round, these two being Guillaume (in red and blue), who now lives in Germany with wife and child, and Benoit (in the middle), still living nearby and still in regular contact.

Security for children

The most important thing for children is to feel loved by their parents, to feel that their parents are united in the face of any childhood traumas and decisions, and to feel safe. It is important that children feel their parents are going to protect them from danger and look after them if they are sick. Wipe away the tears and be ready with cuddles. So moving your children from school to school is not necessarily a good thing, but it is not a bad thing either. In fact, it can be very good for them and it promotes sociability. This was the fourth school our children had attented in as many years. Although I’m not going to pretend that our children shone academically at school – though they held their own – they are now, as adults, all in above-average situations, have plenty of “nouse”, are multi-talented and socially adept. They are also, as the French say, bien dans leur peau. Really, one cannot ask for more.

It goes without saying, perhaps, that they put us through a whole world of teenage traumas, but the main thing was that we always stuck together, through thick and thin, and they always knew and understood their places within the family network. We did things en famille. Moving around gave them broader horizons and an ability to soak-up different situations as and when the needed arose – and they have carried this forward in to adulthood.

Jake holding a kitten named TD, which stood for The Dragon. It is a funny thing, I have never been particularly keen on cats or dogs, but we have almost always had them. The children also had a hamster for a while. It died and I had to dash in to Rochefort to buy another one. One of them commented the hamster looked different … “really ? Hmmm … well, hamsters do change sometimes …” I muttered.

As a child myself I went to fourteen different schools, all over Africa and the South Pacific, Switzerland – and the rest. It never did me any harm, and quite possibly did me a power of good. I always had my parents and my numerous siblings: they were the security net, the familiar faces and the tradition. We made sure it was like this for our children too. The network of the extended family also plays a big role in the life of a child and, bless them, both our families paid regular visits.

Children in France

Quite a lot of things in France were also so different in the handling of children. On the whole French children are polite, know how to behave in a restaurant and, from an early age, are taught how to greet people when they meet – a little hand shake or, frequently, a bisou. This habit of expecting to get a kiss every blessed time a child comes in to contact with an adult (though I don’t mean more than once a day, of course) can, even now, be slightly irritating. Neither Bruce nor I want to kiss children willy-nilly, least of all if they have got a cold. At the first village school children lined up regularly for theirbisou, as childhood good manners dictated, and I decided at a very early stage that, rather than spend most of the morning kissing a row of grubby and snotty little faces (or even darling little faces, because I do like children), I’d simply do an all-British wave.

Our sons, now adults, still kiss-hug their French men friends. They also know about the British manly hand-shake-clap-on-the-shoulder, something which Bruce has always doggedly stuck to (quite right too) regardless of the nationality of the man in question.

Morning view from the patio at Primrose

We moved in to the Chateau des Cypres a few days before Christmas.

I had planned Christmas carefully, and it was supposed to be in Primrose because, although the sale had completed, it was OK by the buyers for us to stay there a few weeks. This was essential to us because Les Cypres was in such a state, and there were fourteen of us for Christmas. At Primrose there was full central heating, bathrooms and toilets, fitted carpets and an operational kitchen.

So it was arranged that Christmas stuff would stay at Primrose for now. Apart from the beds, essential bedding and towels, the Christmas presents and the Christmas food Bruce’s men moved everything, one trailer load at a time to the new house (almost 2 hours’ drive), back and forth, back and forth over two days. I labelled everything carefully, clearly, and stacked things that were to stay all in one place.

But men! You have to love them! Bruce forgot to explain this to his team, and last of all they moved the whole lot, frozen turkey and duvets, Christmas tree and custard, toothbrushes and pillows and saucepans and wine, all piled higgeldy-piggeldy on to the trailer in such a way that Father Christmas himself would have been fazed.

Cross? Oh yes, ooooh yeeees ! I was cross.

old photo of the property, found in a cupboard

It was extremely cold and I declared grimly that I was going to bed and would not be getting out of bed again till there was some central heating. And I meant it! Although I could cope with sacks of plaster where furniture should be, endless wires and pipes and tools, thick dust where stone and brick and timber had been hacked away for whatever reason, I could not cope with the cold.

“I am an African!” I roared down the stair well.

I could deal with walking on planks over the many trenches both inside and out of the property; I could deal with no kitchen of any note, only cold water in the sink, no dishwasher or washing machine yet plumbed in; I could put up with hair like straw because of the dust and children charging around carrying dust even further and adding to the infernal noise of hammers and saws and drills …. but I could not cope with the cold. And it was extremely cold. The house had not been heated for many years – indeed, have never ever been heated thoughout – and the cold permeated the very core of it.

I got in to bed with a hot water bottle and sat there, staring furiously at the wall opposite where forty year-old wallpaper hung in great strands of dusty brown, interspersed with cobwebs and dead insects. Jake clambered in to bed with me – clearly the best place to be.

William, who was then 11, and Bruce had already started on the central heating a few weeks earlier and had promised – PROMISED! – it would be operational by the time we moved in.

“We have accidently moved in two weeks earlier than foreseen,” Bruce tried to reason with me.

“That,” I replied with furious logic, “does not make it any warmer!”

They worked almost all of that first night. Every now and then I was aware of one of them in the room putting a saucepan under a dripping pipe, the sound of electric screwdrivers and drills, and sometimes Bruce cursing. And then – at about four in the morning, the wonderful sound of radiators filling …

Chateau des Cypres when we first saw it. We bought it in 1995 and paid the equivalent of £70 000 for the house, masses of large out-buildings and five acres of land. It had been empty for a very long time and the roof was on the point of going. In fact, Bruce insisted he be allowed to put some trusses and acrow-props in the roof to maintain it before we even signed the initial offer (Compromis de Vente) because it would not have survived another winter.

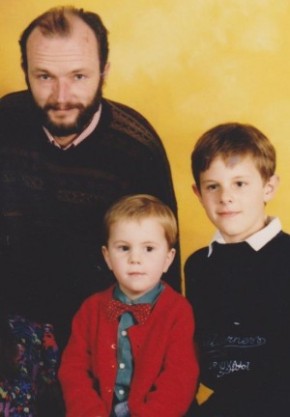

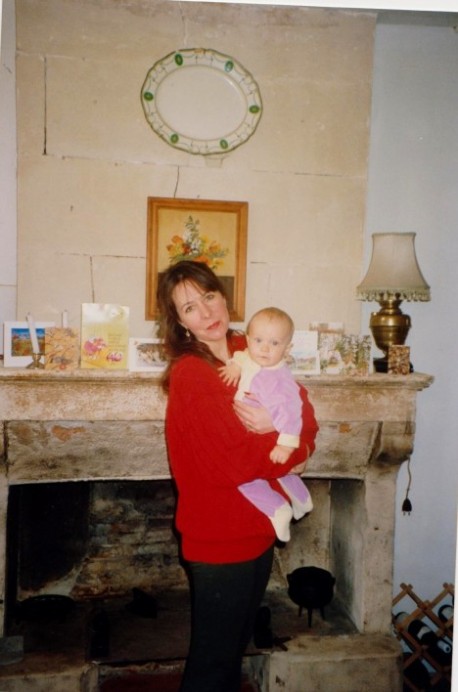

My mother-in-law and the children on Christmas morning. Several bits of fine old furniture, like the bed in this photo, were abandoned in the house. At that time these items were worthless on the French market but almost gold dust for the likes of us. That changed within a year or two and these wonderful old beds and wardrobes are now quite expensive, though anything really big still goes for a song simply because it is generally too big for today’s houses; antiques on the whole now cost considerably more than they do in the UK.

The front of the house when we initially viewed it. One of the first things we did after Completion was open those shutters and leave them open! Many of them were dangerous and had to be removed, almost all were broken – in fact the ones at the two balconies never got put back because re-making them was such a major – and fundamentally unnecessary – chore.

Catherine Broughton is a novelist, a poet and an artist. Her books are available on Amazon/Kindle worldwide, or can be ordered from most leading book stores and libraries. They are also available as e-books (£1.99) on the home page of this site.

– See more at: http://www.turquoisemoon.co.uk/blog/it-happened-like-this-an-english-family-move-to-france-part-10/#sthash.kp7UK5Dh.dpuf